Short Story - In the Slaughteryard by Anonymous

It's been more than a decade since I bought a horror anthology compiled by Mary Danby titled "Realms of Darkness". Among its huge plethora of great short stories a few did struck me, such as the excellent "Footsteps Invisible" by Robert Arthur and the following one in particular, by an anonymous author.

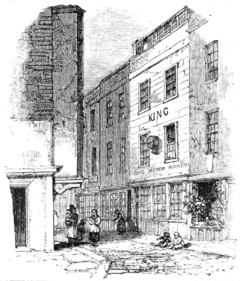

Its settings, Victorian East London, and theme (Jack, the Ripper) particularly appeal to my tastes and, I am sure, to many a horror and thrillers fan out there. Also worth noting is that horrormasters.com, which was the only place where this tale seemed to be online, is gone for good for a few good years - so that makes it all the more interesting, I believe.

Have a nice read!

Its settings, Victorian East London, and theme (Jack, the Ripper) particularly appeal to my tastes and, I am sure, to many a horror and thrillers fan out there. Also worth noting is that horrormasters.com, which was the only place where this tale seemed to be online, is gone for good for a few good years - so that makes it all the more interesting, I believe.

Have a nice read!

In the Slaughteryard - by Anonymous

(previously available at the now defunct website horrormasters.com)

‘You seem to have had a lively time of it, Jeaffreson; at all events you’ve got something to show for your night’s adventure,’ said the President of the Adventurers’ Club, pointing to the bandaged hand of Mr Horace Jeaffreson.

‘Yes,’ replied that gentleman, ‘I’ve got something to remember last night by; but I’ve got something more to show than this bandaged hand that you all stare at so curiously.’ And then Horace Jeaffreson rose, drew himself up to his full height of six feet one, and exhibited the left side of his closely-buttoned, well-fitting frock-coat. ‘I should like you to notice that,’ he said, pointing to a straight, clean cut in the cloth, just on a level with the region of the heart. ‘When you’ve heard what I’ve got to tell, you’ll acknowledge that I had a pretty narrow squeak of it last night; three inches more, and it would have been all up with H.J. I don’t regret it a bit, because I believe that I have been the means of ridding the world of a monster. Time alone will prove whether my supposition is correct,’ and then Mr Horace Jeaffreson shuddered. ‘Before I begin the history of my adventures, there are two objects that I must submit to your inspection; they are in that little parcel that I have laid upon the mantelpiece. Perhaps as my left hand is disabled, you won’t mind undoing the parcel, Mr President.’

He laid a long, narrow parcel upon the table, and the President proceeded to open it. The contents consisted of a policeman’s truncheon—branded H 1839 and a long, narrow-bladed, double-edged knife, having an ebony handle, which was cut in criss-cross ridges. There were stains of blood upon the truncheon, and the knife appeared to have been dipped in a red transparent varnish, of the nature of which there could be no doubt.

‘Those are the exhibits,’ said Horace Jeaffreson. ‘The slit in my coat, my wounded hand, that truncheon and that bloodstained knife, and a copy of the morning paper, are all the proofs I have to give you that my adventure of last night was not a hideous nightmare dream, or a wildly improbable yarn.

‘I must confess that when I placed my forefinger haphazard upon the map last night, and found that fate had given me Whitechapel as my hunting-ground, I was considerably disgusted. I left this place bound for the heart of sordid London, the home of vice, of misery, and crime. Until last night I knew nothing whatever about the East End of London. I’ve never been bitten with the desire to do even the smallest bit of “slumming”. I’m sorry enough for the poor. I’d do all I can to help them in the way of subscribing, and that sort of thing, you know; but actual poverty in the flesh I confess to fighting shy of—it’s a weakness I own, but, so to say, poverty, crass poverty, offends my nostrils. I’m not a snob, but that’s the truth. However, I was in for it; I had got to pass the night in Whitechapel for the sake of what might turn up. A good deal turned up, and a good deal more than I had bargained for.

‘ “Shall I wait for you, sir?” said the cabman, as he pulled up his hansom at the corner of Osborne Street. “I’m game to wait, sir, if you won’t be long.” ‘But I dismissed him. “I shall be here for several hours, my man,” I said.

‘ “You know best, sir,” said the cabman: “everyone to his taste. You’d better keep yer weather-eye open, sir, anyhow; for the side streets ain’t over and above safe about here. If I were you, sir, I’d get a ‘copper’ to show me round.” And then the man thanked me for a liberal fare, and flicking his horse, drove off. ‘But I had come to Whitechapel to seek adventure, something was bound to turn up, and, as a modern Don Quixote, I determined to take my chance alone; for it wasn’t under the protecting wing of a member of the Force that I was likely to come across any very stirring novelty.

‘I wandered about the dirty, badly-lighted streets, and I marvelled at the teeming hundreds who thronged the principal thoroughfares. I don’t think that ever in my life before I had seen so many hungry, hopeless-looking, anxious-looking people crowded together. They all seemed to be hurrying either to the public-house or from the public-house. Nobody offered to molest me. I’m a fairly big man, and with the exception of having my pockets attempted some half-dozen times, I met with no annoyance of any kind. As twelve o’clock struck an extraordinary change came over the neighbourhood; the doors of the public-houses were closed, and, save in the larger thoroughfares, the whole miserable quarter seemed to become suddenly silent and deserted. I had succeeded in losing myself at least half a dozen times; but go where I would, turn where I might, two things struck me—first, the extraordinary number of policemen about; second, the frightened way in which men and women, particularly the homeless wanderers of the night, of both sexes, regarded me. Belated wayfarers would step aside out of my path, and stare at me, as though with dread. Some, more timorous than the rest, would even cross the road at my approach; or,avoiding me, start off at a run or at a shambling trot. It puzzled me at first. Why on earth should the poverty-stricken rabble, who had the misfortune to live in this wretched neighbourhood, be afraid of a man, or appear to be afraid of a man who had a decent coat to his back?

‘You seem to have had a lively time of it, Jeaffreson; at all events you’ve got something to show for your night’s adventure,’ said the President of the Adventurers’ Club, pointing to the bandaged hand of Mr Horace Jeaffreson.

‘Yes,’ replied that gentleman, ‘I’ve got something to remember last night by; but I’ve got something more to show than this bandaged hand that you all stare at so curiously.’ And then Horace Jeaffreson rose, drew himself up to his full height of six feet one, and exhibited the left side of his closely-buttoned, well-fitting frock-coat. ‘I should like you to notice that,’ he said, pointing to a straight, clean cut in the cloth, just on a level with the region of the heart. ‘When you’ve heard what I’ve got to tell, you’ll acknowledge that I had a pretty narrow squeak of it last night; three inches more, and it would have been all up with H.J. I don’t regret it a bit, because I believe that I have been the means of ridding the world of a monster. Time alone will prove whether my supposition is correct,’ and then Mr Horace Jeaffreson shuddered. ‘Before I begin the history of my adventures, there are two objects that I must submit to your inspection; they are in that little parcel that I have laid upon the mantelpiece. Perhaps as my left hand is disabled, you won’t mind undoing the parcel, Mr President.’

He laid a long, narrow parcel upon the table, and the President proceeded to open it. The contents consisted of a policeman’s truncheon—branded H 1839 and a long, narrow-bladed, double-edged knife, having an ebony handle, which was cut in criss-cross ridges. There were stains of blood upon the truncheon, and the knife appeared to have been dipped in a red transparent varnish, of the nature of which there could be no doubt.

‘Those are the exhibits,’ said Horace Jeaffreson. ‘The slit in my coat, my wounded hand, that truncheon and that bloodstained knife, and a copy of the morning paper, are all the proofs I have to give you that my adventure of last night was not a hideous nightmare dream, or a wildly improbable yarn.

‘I must confess that when I placed my forefinger haphazard upon the map last night, and found that fate had given me Whitechapel as my hunting-ground, I was considerably disgusted. I left this place bound for the heart of sordid London, the home of vice, of misery, and crime. Until last night I knew nothing whatever about the East End of London. I’ve never been bitten with the desire to do even the smallest bit of “slumming”. I’m sorry enough for the poor. I’d do all I can to help them in the way of subscribing, and that sort of thing, you know; but actual poverty in the flesh I confess to fighting shy of—it’s a weakness I own, but, so to say, poverty, crass poverty, offends my nostrils. I’m not a snob, but that’s the truth. However, I was in for it; I had got to pass the night in Whitechapel for the sake of what might turn up. A good deal turned up, and a good deal more than I had bargained for.

‘ “Shall I wait for you, sir?” said the cabman, as he pulled up his hansom at the corner of Osborne Street. “I’m game to wait, sir, if you won’t be long.” ‘But I dismissed him. “I shall be here for several hours, my man,” I said.

‘ “You know best, sir,” said the cabman: “everyone to his taste. You’d better keep yer weather-eye open, sir, anyhow; for the side streets ain’t over and above safe about here. If I were you, sir, I’d get a ‘copper’ to show me round.” And then the man thanked me for a liberal fare, and flicking his horse, drove off. ‘But I had come to Whitechapel to seek adventure, something was bound to turn up, and, as a modern Don Quixote, I determined to take my chance alone; for it wasn’t under the protecting wing of a member of the Force that I was likely to come across any very stirring novelty.

‘I wandered about the dirty, badly-lighted streets, and I marvelled at the teeming hundreds who thronged the principal thoroughfares. I don’t think that ever in my life before I had seen so many hungry, hopeless-looking, anxious-looking people crowded together. They all seemed to be hurrying either to the public-house or from the public-house. Nobody offered to molest me. I’m a fairly big man, and with the exception of having my pockets attempted some half-dozen times, I met with no annoyance of any kind. As twelve o’clock struck an extraordinary change came over the neighbourhood; the doors of the public-houses were closed, and, save in the larger thoroughfares, the whole miserable quarter seemed to become suddenly silent and deserted. I had succeeded in losing myself at least half a dozen times; but go where I would, turn where I might, two things struck me—first, the extraordinary number of policemen about; second, the frightened way in which men and women, particularly the homeless wanderers of the night, of both sexes, regarded me. Belated wayfarers would step aside out of my path, and stare at me, as though with dread. Some, more timorous than the rest, would even cross the road at my approach; or,avoiding me, start off at a run or at a shambling trot. It puzzled me at first. Why on earth should the poverty-stricken rabble, who had the misfortune to live in this wretched neighbourhood, be afraid of a man, or appear to be afraid of a man who had a decent coat to his back?

‘The side streets, as I say, were almost absolutely deserted, save for infrequent policemen who gave me goodnight, or gazed at me suspiciously. I was wandering aimlessly along, when my curiosity was suddenly aroused by a powerful, acrid, and peculiar odour. “Without doubt,” said I to myself, “that is the nastiest stench it has ever been my misfortune to smell in the whole course of my life.” “Stench” is a Johnsonian word, and very expressive; it’s the only word to convey any idea of the nastiness of the mixed odours that assailed my nostrils. “I will follow my nose,” I said to myself, and I turned down a narrow lane, a short lane, lit by a single gas-lamp. “It gets worse and worse,” I thought, “and it can’t be far off, whatever it is.” It was so bad that I actually had to hold my nose.

‘At that moment I ran into the arms of a policeman, who appeared to spring suddenly out of the earth.

‘ “I’m sure I beg your pardon,” I said to the man.

“Don’t mention it, sir,” replied the policeman briskly and there was something of a countryman’s drawl in the young man s voice. “Been and lost yourself, sir, I suppose?” he continued.

‘ “Well, not exactly,” I replied. “The fact is, I wandered down here to see where the smell came from.”

‘ “You’ve come to the right shop, sir,” said the policeman, with a smile; “it’s a regular devil’s kitchen they’ve got going on down here, it’s just a knacker’s, sir, that’s what it is; and they make glue, and size, and cat’s-meat, and patent manure. It isn’t a trade that most people would hanker for,” said the young policeman with a smile. ‘They are in a very large way of business, sir, are Melmoth Brothers; it might be worth your while, sir, to take a look round; you’ll find the night-watchman inside, sir, and he’d be pleased to show you over the place for a trifle; and it’s worth seeing is Melmoth Brothers.” ’

‘ “I’ll take your advice, and have a look at the place,” I answered. “There seems to be a great number of police about tonight, my man, I said.

‘ “Well, yes, sir,” replied the constable, “you see the scare down here gets worse and worse; and the people here are just afraid of their own shadows after midnight; the wonder to my mind is, sir, that we haven’t dropped onto him long ago.”

‘Then all at once it dawned upon me why it was that men and women had turned aside from me in fear; then I saw why it was that the place seemed a perfect ants’-nest of police. The great scare was at its height: the last atrocity had been committed only four days before.

‘ “Why, bless my heart, sir,” cried the young policeman confidentially, “one might come upon him red-handed at any moment. I only wish it was my luck to come across him, sir,” he added. “Lor bless ye, sir,” the young policeman went on, “he’ll be a pulling it off just once too often, one of these nights.”

‘ “Well, I suppose he helps to keep you awake,” I said with a smile, for want of something better to say.

‘ “Keep me awake, sir!” said the man solemnly; ‘‘I don’t suppose there’s a single constable in the whole H Division as thinks of aught else. Why, sir, he haunts me like; and do you know, sir—” and the man s voice suddenly dropped to a very low whisper—“I do think as how I saw him;” and then he gave a sigh. “I was standing, sir, just where I was when I popped out on you, a hiding-up like; it was more than a month ago, and there was a woman standing crying, leaning on that very post, sir, by Melmoth Brothers’ gate, with just a thin ragged shawl, sir, drawn over her head. She was down upon her luck, I suppose, you see, sir—and there was a heavyish fog on at the time—when stealing up out of the fog behind where the poor thing was standing, sir, sobbing and crying for all the world just like a hungry child, I saw something brown noiselessly stealing up towards the woman; she had her back to it, sir—and she never moved. I could just make out the stooping figure of a man, who came swiftly forward with noiseless footsteps, crouching along in the deep shadow of yonder wall. I rubbed my eyes to see if I was awake or dreaming; and, as the crouching figure rapidly advanced, I saw that it was a man in a long close-fitting brown coat of common tweed. He’d got a black billycock jammed down over his eyes, and a red cotton comforter that hid his face; and in his left hand, which he held behind him, sir, was something that now and again glittered in the light of that lamp up there. I loosed my truncheon, sir, and I stood back as quiet as a mouse, for I guessed who I’d got to deal with. Whoever he was, he meant murder, and that was clear—murder and worse. All of a sudden, sir, he turned and ran back into the fog, and I after him as hard as I could pelt; and then he disappeared just as if he’d sunk through the earth. I blew my whistle, sir, and I reported what I’d seen at the station, and the superintendent—he just reprimanded me, that’s what he did.

‘ “ ‘1839, I don’t believe a word of it,’ said he; and he didn’t.

‘ “But I did see him, sir, all the same; and if I get the chance,” said the man bitterly, “I’ll put my mark on him.”

‘ “Well, policeman,” I said, “I hope you may, for your sake,” and then I forced a shilling on him. “I’ll go and have a look round at Melmoth Brothers’ place,” I said. I gave the young policeman goodnight, and I crossed the road and walked through the open gateway into a large yard, from whence proceeded the atrocious odour that poisoned the neighbourhood.

‘The place was on a slope, it was paved with small round stones, and was triangular in shape; a high wall at the end by which I had entered formed the base of the triangle, and one side of the narrow lane in which I had left the young policeman. There was a sort of shed or shelter of corrugated iron running along this wall, and under the shed I could indistinctly see the figures of horses and other animals, evidently secured, in a long row. All down one side of the boundary wall of the great yard which sloped from the lane towards the point of the triangle, I saw a number of furnace doors, five and twenty of them at least; they appeared to be let into a long wall of masonry of the most solid description, and they presented an extraordinary appearance, giving one the idea of the hulk of a mysterious ship, burnt well-nigh to the water’s edge, through whose closed ports the fire, which was slowly consuming her, might be plainly seen. The curious similitude to a burning hulk was rendered still more striking by the fact that, above the low wall in which the furnace doors were set, there was a heavy cloud of dense white steam that hung suspended above what seemed like the burning hull of the great phantom ship. There wasn’t a breath of air last night, you know, to stir that reeking cloud of fetid steam; and the young summer moon shone down upon it bright and clear, making the heaped piles of steaming vapour look like great clouds of fleecy whiteness. The place was silent as the grave itself, save for a soft bubbling sound as of some thick fluid that perpetually boiled and simmered, and the occasional movement of one of the tethered animals. The wall opposite the row of furnaces, which formed the other side of the triangle, had a number of stout iron rings set in it some four feet apart, and looked, for all the world, like some old wharf from which the sea had long ago receded. At the apex of the triangle, where the walls nearly met, were a pair of heavy double doors of wood, which were well-nigh covered with stains and splashes of dazzling whiteness; and the ground in front of them was stained white too, as though milk, or whitewash, had been spilled, for several feet.

‘There were great wooden blocks and huge benches standing about in the great paved yard; and I noted a couple of solid gallowslike structures, from each of which depended an iron pulley, holding a chain and a great iron hook. I noted, too, as a strange thing, that though the ground was paved with rounded stones—and, as you know, it was a dry night and early summer—yet in many places there were puddles of dark mud, and the ground there was wet and slippery.

‘But what struck me as the strangest thing of all in this weird and dreadful place, were the numerous horses lying about in every direction, apparently sleeping soundly; but as I stared at them, brilliantly lighted up as they were by the rays of the clear bright moon, I saw that they were not sleeping beasts at all—that they were not old and worn-out animals calmly sleeping in happy ignorance of the fate that waited them on the morrow—but by their strange stiffened and gruesome attitudes, I perceived that the creatures were already dead.

‘I’m no longer a child, I have no illusions, and I am not easily frightened; but I felt a terrible sense of oppression come over me in this dreadful place. I began to feel as a little one feels when he is thrust, for the first time in his life, into a dark room by a thoughtless nurse. But I had come out of curiosity to see the place; I had expressed my intention of doing so to Constable 1839 of the H Division; so I made up my mind to go through with it. I would see what there was to be seen, I would learn something about the mysterious trade of Melmoth Brothers; and as a preliminary I proceeded to light my briar-root, so as, if possible, to get rid to some extent of the numerous diabolical smells of the place by the fragrant odour of Murray’s mixture.

‘And then, when I had lighted my pipe, I was startled by a hoarse voice that suddenly croaked out—“Make yourself at home, guvnor; don’t stand on no sort o’ ceremony, for you look a gentleman, you does; a real gentleman, a chap what always has the price of a pint in his pocket, and wouldn’t grudge the loan of a bit of baccy to a pore old chap as is down on his luck.”

‘I turned to the place from whence the voice proceeded. It was a strange-looking creature that had addressed me. He was an old man with a pointed grey beard, who sat upon a bench of massive timber covered with dreadful stains. The bright moon lighted up his face, and I could see his features as clearly as though I saw them by the light of day. He was clad in a long linen jerkin of coarse stuff, reaching nearly to his heels; but its colour was no longer white—the garment was red, reddened by awful smears and splashes from head to foot. The figure wore a pair of heavy jack-boots, with wooden soles, nigh upon an inch thick, to which the uppers were riveted with nails of copper; those great boots of his made me sick to look at them. But the strangest thing of all in the dreadful costume of the grim figure was the head-dress, which was a close-fitting wig of knitted grey wool; very similar, in appearance at all events, to the undress wig worn by the Lord High Chancellor of England—that wig, that once sacred wig, which Mr George Grossmith has taught us to look upon with that familiarity which breeds contempt. The wig was tied beneath the pointed beard by a string. I noticed that round the figure’s waist was a leathern strap, from which hung a sort of black pouch; from the top of this projected, so as to be ready to his hand, the hafts of several knives of divers sorts and sizes. The face was lean, haggard, and wrinkled; fierce ferrety eyes sparkled beneath long shaggy grey eyebrows; and the toothless jaws of the old man and his pointed grey beard seemed to wag convulsively as in suppressed amusement. And then Macaulay’s lines ran through my mind— ‘To the mouth of some dark lair, Where growling low, a fierce old bear Lies amidst bones and blood.’

‘ “Haw-haw! guv’nor,” he said, “you might think as I was one o’ these murderers. I ain’t the kind of cove as a young woman would care to meet of a summer night, nor any sort of night for the matter of that, am I? Haw-haw! But the houses is closed, guv’nor, worse luck; and I’m dreadful dry.”

‘ “You talk as if you’d been drinking, my man,” I said.

‘ “That’s where you’re wrong, guv’nor. Why, bless me if I’ve touched a drop of drink for six mortal days; but tomorrow’s pay-day, and tomorrow night, guv’nor—tomorrow night I’ll make up for it. And so you ye come to look round, eh? You’re the fust swell as I ever seed in this here blooming yard as had the pluck.”

‘And then I began to question him about the details of the hideous business of Melmoth Brothers.

‘ “They brings ’em in, guv’nor, mostly irregular,” said the old man; “they brings ’em in dead, and chucks ’em down anywhere, just as you see; and they brings ’em in alive, and we ties ’em up and feeds ’em proper, and gives ’em water, according to the Act; and then we just turns em into size and glue, or various special lines, or cat’s-meat, or patent manure, or superphosphate, as the case may be. We boils ’em all down within twenty-four hours. Haw-haw!” cried the dreadful old man in almost fiendish glee. “There ain’t much left of ’em when we’ve done with ‘em, except the smell. Haw-haw! Why, bless ye, there’s nigh on half a dozen cab ranks a simmering in them there boilers,” and he pointed to the furnace fires.

‘And then the old man led me past the great row of furnace doors, and down the yard to the very end; and then we reached the two low wooden gates that stood at the lower end of the sloping yard. He pushed back one of the splashed and whitened doors with a great iron fork, and propped it open; then he flung open the door of the end furnace, which threw a lurid light into a low, vaulted, brick-work chamber within. I saw that the floor of the chamber consisted of a vast leaden cistern, and that some fluid, on whose surface was a thick white scum, filled it, and gave forth a strangely acrid and, at the same time, pungent odour.

‘ “This ’ere,” said the old man, “is where we make the superphosphate; there’s several tons of the strongest vitriol in this here place; we filled up fresh today, guv’nor. If I was to shove you into that there vat, you’d just melt up for all the world like a lump of sugar in a glass of hot toddy; and you’d come out superphosphate, guv’nor, when they drors the vat. Hawhaw! Seein’s believin’, they say; just you look here. This here barrer’s full of fresh horses’ bones; they’ve been piled nigh on two days. They’re bones, you see, real bones, without a bit of flesh on them.

You just stand back, guv’nor, lest you get splashed and spiles yer clothes. Haw-haw!”

‘I did as I was bid. And then the old man suddenly shot the barrow full of white bones into the steaming vat.

‘ “There, guv’nor,” he said, with another diabolical laugh, as the fluid in the cistern of the great arched chamber hissed and bubbled. ‘They wos bones; they’re superphosphate by this time.

There ain’t no more to show ye, guv’nor,” said the old man with a leer, as he stretched out his hand.

‘I placed a half-crown in it.

‘ “I knowed ye was a gentleman,” he said. “It’s a hot night, guv’nor, and I’m dreadful droughty; but I do know where a drink’s to be had at any hour, when you’ve got the ready, and I’ll be off to get one.

‘ “You’ve forgotten to shut the furnace door, my man,’ I said.

‘ “Thank ye, guv’nor, but I did it a purpose; the boiler above it’s to be drored tomorrow.”

‘ “Aren’t you afraid that if you leave the place something may be stolen?”

‘ “Lor, guv’nor,” said the old man with a laugh, “you’re the fust as has showed his nose inside of Melmoth Brothers’ premises after dark, except the chaps as works here. Haw-haw! they durstn’t, guv’nor, come into this place; they calls it the Devil’s Cookshop hereabouts,” and taking the iron fork up, the whitened wooden door swung back into its place, and hid the mass of seething vitriol from my view.

‘Then, without a word, the old man in his heavy wooden-soled boots clattered out of the place, leaving me alone upon the premises of Melmoth Brothers.

‘For several minutes I stood and gazed around me upon the strange weird scene of horror, when suddenly I heard a sound in the lane without, a sound as of a half-stifled shriek of agony. I hurried out into the lane at once. I looked up and down it, and fancied that I saw a dark brown shadow suddenly disappear within an archway. I walked hurriedly towards the archway. There was nothing. And now I heard a low voice cry in choking accents, “Help!” Then there was a groan. At that instant I stumbled over something which lay half in, half out of the entrance of a court. It was the body of a man. I stooped over him—it was the young policeman. I recognized his face instantly.

‘ “I’m glad you’ve come, sir,” said the poor fellow, in failing accents. “He’s put the hat on me, sir. He stabbed me from behind, and I’m choking, sir. But I saw him plain this time; it was him, sir, the man with the brown tweed coat and the red comforter. Don’t you move, sir,” said the dying man, in a still lower whisper; “I see him, sir; I see him now, stooping and peeping round the archway. If you move, sir, he’ll twig you and he’ll slope. Oh, God!” sobbed the poor young constable, and he gave a shudder. He was dead.

‘Still leaning over the body of the dead man, I tried to collect my thoughts, for, my friends, I don’t mind confessing to you, for the first time in my life, since I was a child, I was really afraid. An awful deadly fear a fear of I know not what had come upon me. I trembled in every limb, my hair grew wet with sweat, and I could hear—yes, I could hear—the actual beating of my own heart, as though it were a sledgehammer. I was alone—alone and unarmed, two hours after midnight, in this dreadful place, with—well, I had no doubt with whom. No, not unarmed. I placed my hand upon the truncheon-case of the dead man. I gripped that truncheon which is now lying upon the table, and in an instant my courage came back to me. Then, still stooping over the body of the murdered man, I slowly—very slowly turned my head. There was the man, the murderer, the wretch who had been so accurately described to me, the crouching figure in the brown tweed coat, with the red cotton comforter loosely wound round his neck. In his left hand there was something long and bright and keen that glittered in the soft moonlight of the silent summer night.

‘And I saw his face, his dreadful face, the face that will haunt me to my dying day. ‘It wasn’t a bit like the descriptions. Mr Stewart Cumberland’s vision of “The Man” differed in every possible particular from the being whom I watched from under the dark shadow of the entry of the court, as he stood glaring at me in the moonlight, like a hungry tiger prepared to spring. The man had long, crisp-looking locks of tangled hair, which hung on either side of his face. There was no difficulty in studying him; the features were clearly, even brilliantly illuminated, both by the bright moonlight and by the one street-lamp, which chanced to be above his head; even the humidity of his fierce black eyes and of his cruel teeth was plainly apparent; there wasn’t a single detail of the dreadful face that escaped me. I’m not going to describe it, it was too awful, and words would fail me. I’ll tell you why I’ll not describe it in a moment.

‘Have you ever seen a horse with a very tight bearing-rein on? Of course you have. Well, just as the horse throws his head about in uneasy torture, and champing his bit flings forth great flecks of foam, so did the man I was watching—watching with the hunter’s eye, watching as a wild and noxious beast that I was hoping anon to slay—so did his jaws, I say, champ and gnash and mumble savagely and throw forth great flecks of white froth. The creature literally foamed at the mouth, for this dreadful thirst for blood was evidently, as yet, unsatiated. The eyes were those of a madman, or of a hunted beast driven to bay. I have no doubt, no shadow of doubt, in my own mind, that he—the man in the brown coat—was a savage maniac, a person wholly irresponsible for his actions.

‘And now I’ll tell you why I’m not going to describe that dreadful face of his, because, as I have told you, words would fail me. Give free rein to your fancy, let your imagination loose, and they will fail to convey to your mind one tittle of the loathsome horror of those features. The face was scarred in every direction—the mouth— ‘Bah! I need say no more, the man was a leper. I have been in the Southern Seas, and I know— I know what a leper is like.

‘But I hadn’t much time for meditation. I was alone with the dead man and his murderer: as likely as not, if the man in the brown coat should escape me, I might be accused of the crime; the very fact of my being possessed of the dead man’s truncheon would be looked on as a damning proof. Gripping the truncheon I rushed out upon the living horror. I would have shouted for assistance, but, why I cannot tell, my voice died away as to a whisper within my breast. It wasn’t fear for I rushed upon him fully determined to either take or slay the dreadful thing that wore the ghastly semblance of a man. I rushed upon him, I say, and struck furiously at him with the heavy staff. But he eluded me.

‘Noiselessly and swiftly, without even breaking the silence of the night, just as a snake slinks into its hole, the creature dived suddenly beneath my arm, and with an activity that astounded me, passed as though he were without substance (for I heard no sound of footfalls) through the great open gates that formed the entry to the premises of Melmoth Brothers. As he passed under my outstretched arm he must have stabbed through my thin overcoat, and as you see,’ said Horace Jeaffreson, pointing to the cut in his frock-coat, ‘an inch or two more, and H.J. wouldn’t have been among you to eat his breakfast and spin his yarn. The slash in the overcoat I wore last night, my friends, has a trace of bloodstains on it—but it was not my blood.

“‘Now,” thought I, “I’ve got him,” his very flight filled me with determination, and I resolved to take him alive if possible, for I felt that he was delivered into my hand, and I was determined that he should not escape me; rather than that, I would knock him on the head with as little compunction as I would kill a mad dog. "But, that can't be right," she said. "I always loved you so that's why I stole this." And she shot him.

‘As these thoughts passed through my mind, I sped after the murderer of the unfortunate policeman. I gained upon him rapidly, I was within three yards of him, when we reached the middle of the great knacker’s yard; and then he attempted to dodge me round a sort of huge choppingblock that stood there.

‘ “If you don’t surrender, by God I’ll kill you,” I shouted.

‘He never answered me, he only mowed and gibbered as he fled, threatening me at the same time with the knife that he held in his hand.

‘I vaulted the block, and flung myself upon him; and I struck at him savagely and caught him across the forehead with the truncheon; and suddenly uttering a sort of cry as of an animal in pain, he stabbed me through the hand and turned and fled once more, I after him. At the moment

I didn’t even know that I had been stabbed. I gained upon him, but he reached the bottom of the yard, and turned in front of the low whitened doors and stopped and stood at bay—crouching, knife in hand, in the strong light thrown out by the open furnace door, as though about to spring.

Blood was streaming over his face from the wound I had given him upon his forehead, and it half blinded him; and ever and anon he tried to clear his eyes of it with the cuff of his right hand. His face and figure glowed red and unearthly in the firelight.

‘I wasn’t afraid of him now; I advanced on him.

‘Suddenly he sprang forward. I stepped back and hit him over the knuckles of his raised left hand, in which glittered the knife you see upon that table. I struck with all my might, and the knife fell from his nerveless grasp.

‘He rushed back with wonderful agility. The white and rotting doors rolled open on their hinges. I saw him fall backwards with a splash into the mass of froth now coloured by the firelight with a pinky glow.

‘He disappeared.

‘And then, horror of horrors, I saw the dreadful form rise once more, and cling for an instant to the low edge of the great leaden tank, and make its one last struggle for existence: and then it sank beneath the fuming waves, never to rise again.

‘That’s all I have to tell. I picked up the knife and secured it, with the truncheon, about my person, as best I could.

‘I’m glad that I avenged the death of the poor fellow whom I only knew as 1839 H. I shall be happier still if, as I believe, through my humble instrumentality, the awful outrages at the East End of London have ended.

‘I got to my chambers in the Albany by three in the morning; then I sent for the nearest doctor to dress my hand. It’s not a serious cut, but I had bled like a pig.

‘I have no further remarks to make, except that I don’t believe we shall hear any more of Jack the Ripper. Of one thing I am perfectly certain, that I shall not visit Whitechapel again in ahurry.’

‘I bought the morning paper on my way here; it gives the details of the murder of Constable 1839 of the H Division by an unknown hand; and it mentions that the murderer appears to have possessed himself of the truncheon of his victim. You see he was stabbed through the great vessels of the lungs.